Clement-Jones family - Person Sheet

Clement-Jones family - Person Sheet

Spouses

1Mary MOFFATT, 3607

FatherRobert MOFFATT , 3608

ChildrenAnna Mary , 3605 (1858-)

Agnes , 3610 (1847-)

Robert , 3611

Thomas , 3612

William Oswell , 3613 (1851-)

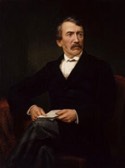

Notes for Dr David LIVINGSTONE

A Scottish Congregationalist pioneer medical missionary with the London Missionary Society and explorer in Africa. His meeting with H. M. Stanley gave rise to the popular quotation, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?".

Perhaps one of the most popular national heroes of the late 19th century in Victorian Britain, Livingstone had a mythic status, which operated on a number of interconnected levels: that of Protestant missionary martyr, that of working-class "rags to riches" inspirational story, that of scientific investigator and explorer, that of imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of commercial empire.

His fame as an explorer helped drive forward the obsession with discovering the sources of the River Nile that formed the culmination of the classic period of European geographical discovery and colonial penetration of the African continent. At the same time his missionary travels, "disappearance" and death in Africa, and subsequent glorification as posthumous national hero in 1874 led to the founding of several major central African Christian missionary initiatives carried forward in the era of the European "Scramble for Africa."

David Livingstone was born on March 19, 1813 in the mill town of Blantyre, beside the bridge crossing into Bothwell, Lanarkshire, Scotland, into a Protestant family believed to be descended from the highland Livingstones, a clan that had been previously known as the Clan MacLea. Born to Neil Livingstone (1788–1856) and his wife Agnes (1782–1865), David, along with many of the Livingstones, was at the age of ten employed in the cotton mill of H. Monteith – David and brother John working 12-hour days as "piecers," tying broken cotton threads on the spinning machines. The mill offered their workers schooling of which David took advantage.

Livingstone's father Neil was very religious, a Sunday School teacher and teetotaller who handed out Christian tracts on his travels as a door to door tea salesman, and who read books on theology, travel and missionary enterprises. This rubbed off on the young David, who became an avid reader, but he also loved scouring the countryside for animal, plant and geological specimens in local limestone quarries. Neil Livingstone had a fear of science books as undermining Christianity and attempted to force him to read nothing but theology, but David's deep interest in nature and science led him to investigate the relationship between religion and science.[3] When in 1832 he read Philosophy of a Future State by the science teacher, amateur astronomer and church minister Thomas Dick, he found the rationale he needed to reconcile faith and science, and apart from the Bible this book was perhaps his greatest philosophical influence.

Other significant influences in his early life were Thomas Burke, a Blantyre evangelist and David Hogg, his Sunday School teacher. At age nineteen David and his father left the Church of Scotland for a local Congregational church, influenced by preachers like Ralph Wardlaw who denied predestinatarian limitations on salvation. Influenced by American revivalistic teachings, Livingstone's reading of the missionary Karl Gützlaff's "Appeal to the Churches of Britain and America on behalf of China" enabled him to persuade his father that medical study could advance religious ends.

Livingstone's experience from age 10 to 26 in H. Montieth's Blantyre cotton mill, first as a piecer and later as a spinner, was also important. Necessary to support his impoverished family, this work was monotonous but gave him persistence, endurance, and a natural empathy with all who labour, as expressed by lines he used to hum from the egalitarian Rabbie Burns song: "When man to man, the world o'er / Shall brothers be for a' that".

Livingstone attended Blantyre village school along with the few other mill children with the endurance to do so, but a family with a strong, ongoing commitment to study also reinforced his education. . After reading Gutzlaff's appeal for medical missionaries for China in 1834, he began saving money and in 1836 entered Anderson's College in Glasgow, founded to bring science and technology to ordinary folk, and attended Greek and theology lectures at the University of Glasgow. In addition, he attended divinity lectures by Wardlaw, a leader at this time of vigorous anti-slavery campaigning in the city. Shortly after he applied to join the London Missionary Society (LMS) and was accepted subject to missionary training. He continued his medical studies in London while training there and in Essex to be a minister under LMS. Despite his impressive personality, he was a poor preacher and would have been rejected by the LMS had not the Director given him a second chance to pass the course.

Livingstone hoped to go to China as a missionary, but the First Opium War broke out in September 1839 and the LMS suggested the West Indies instead. In 1840, while continuing his medical studies in London, Livingstone met LMS missionary Robert Moffat, on leave from Kuruman, a missionary outpost in South Africa, north of the Orange River. Excited by Moffat's vision of expanding missionary work northwards, and influenced by abolitionist T.F. Buxton's arguments that the African slave trade might be destroyed through the influence of "legitimate trade" and the spread of Christianity; Livingstone focused his ambitions on Southern Africa.

He was deeply influenced by Moffat's judgment that he was the right person to go to the vast plains to the north of Bechuanaland, where he had glimpsed "the smoke of a thousand villages, where no missionary had ever been".

Perhaps one of the most popular national heroes of the late 19th century in Victorian Britain, Livingstone had a mythic status, which operated on a number of interconnected levels: that of Protestant missionary martyr, that of working-class "rags to riches" inspirational story, that of scientific investigator and explorer, that of imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of commercial empire.

His fame as an explorer helped drive forward the obsession with discovering the sources of the River Nile that formed the culmination of the classic period of European geographical discovery and colonial penetration of the African continent. At the same time his missionary travels, "disappearance" and death in Africa, and subsequent glorification as posthumous national hero in 1874 led to the founding of several major central African Christian missionary initiatives carried forward in the era of the European "Scramble for Africa."

David Livingstone was born on March 19, 1813 in the mill town of Blantyre, beside the bridge crossing into Bothwell, Lanarkshire, Scotland, into a Protestant family believed to be descended from the highland Livingstones, a clan that had been previously known as the Clan MacLea. Born to Neil Livingstone (1788–1856) and his wife Agnes (1782–1865), David, along with many of the Livingstones, was at the age of ten employed in the cotton mill of H. Monteith – David and brother John working 12-hour days as "piecers," tying broken cotton threads on the spinning machines. The mill offered their workers schooling of which David took advantage.

Livingstone's father Neil was very religious, a Sunday School teacher and teetotaller who handed out Christian tracts on his travels as a door to door tea salesman, and who read books on theology, travel and missionary enterprises. This rubbed off on the young David, who became an avid reader, but he also loved scouring the countryside for animal, plant and geological specimens in local limestone quarries. Neil Livingstone had a fear of science books as undermining Christianity and attempted to force him to read nothing but theology, but David's deep interest in nature and science led him to investigate the relationship between religion and science.[3] When in 1832 he read Philosophy of a Future State by the science teacher, amateur astronomer and church minister Thomas Dick, he found the rationale he needed to reconcile faith and science, and apart from the Bible this book was perhaps his greatest philosophical influence.

Other significant influences in his early life were Thomas Burke, a Blantyre evangelist and David Hogg, his Sunday School teacher. At age nineteen David and his father left the Church of Scotland for a local Congregational church, influenced by preachers like Ralph Wardlaw who denied predestinatarian limitations on salvation. Influenced by American revivalistic teachings, Livingstone's reading of the missionary Karl Gützlaff's "Appeal to the Churches of Britain and America on behalf of China" enabled him to persuade his father that medical study could advance religious ends.

Livingstone's experience from age 10 to 26 in H. Montieth's Blantyre cotton mill, first as a piecer and later as a spinner, was also important. Necessary to support his impoverished family, this work was monotonous but gave him persistence, endurance, and a natural empathy with all who labour, as expressed by lines he used to hum from the egalitarian Rabbie Burns song: "When man to man, the world o'er / Shall brothers be for a' that".

Livingstone attended Blantyre village school along with the few other mill children with the endurance to do so, but a family with a strong, ongoing commitment to study also reinforced his education. . After reading Gutzlaff's appeal for medical missionaries for China in 1834, he began saving money and in 1836 entered Anderson's College in Glasgow, founded to bring science and technology to ordinary folk, and attended Greek and theology lectures at the University of Glasgow. In addition, he attended divinity lectures by Wardlaw, a leader at this time of vigorous anti-slavery campaigning in the city. Shortly after he applied to join the London Missionary Society (LMS) and was accepted subject to missionary training. He continued his medical studies in London while training there and in Essex to be a minister under LMS. Despite his impressive personality, he was a poor preacher and would have been rejected by the LMS had not the Director given him a second chance to pass the course.

Livingstone hoped to go to China as a missionary, but the First Opium War broke out in September 1839 and the LMS suggested the West Indies instead. In 1840, while continuing his medical studies in London, Livingstone met LMS missionary Robert Moffat, on leave from Kuruman, a missionary outpost in South Africa, north of the Orange River. Excited by Moffat's vision of expanding missionary work northwards, and influenced by abolitionist T.F. Buxton's arguments that the African slave trade might be destroyed through the influence of "legitimate trade" and the spread of Christianity; Livingstone focused his ambitions on Southern Africa.

He was deeply influenced by Moffat's judgment that he was the right person to go to the vast plains to the north of Bechuanaland, where he had glimpsed "the smoke of a thousand villages, where no missionary had ever been".